KIMS Periscope 제303호

북극해 항로 – 산업과 안보, 한국에 주는 시사점

기후변화로 인해 물리적 및 정치적 측면에서 북극이 개방되었다. 인간 활동이 증가하면서 물리적으로 북극길이 열렸고 정치적 개방으로 국제적 이권이 발생했으나, 국제 정세에 영향을 받게 되었다.

한국 역시 2000년대 중반 부상하기 시작한 ‘새로운 북극 (new Arctic)’에 관심을 갖기 시작했다. 한국은 2008년 북극이사회 (Arctic Council)의 옵서버 지위를 신청했고, 2013년부터 정식 옵서버로 활동을 시작해 2013년과 2018년에는 북극 정책기본계획을 발간했다. 세계 최대 운송 및 조선산업을 영위하는 대표적인 국가인 한국의 야심찬 목표를 보여주는 증거라고 할 수 있다. 북극은 유럽 시장과의 거리를 단축시키는 대안 항로일 뿐만 아니라, 한국 선박업에 흥미로운 시장이기도 하다.

짧은 본 글에서는 북극 항해의 미래에 대한 명확한 비전을 제시하는 대신, 미래 전망 형성에 있어 이전부터 중요하게 작용했고, 앞으로도 중요한 요소로 고려될 비즈니스와 안보 측면을 분석한다. 비즈니스와 안보 측면 모두 중장기적으로 북극 해상운송이 크게 성장할 것임을 알려주고 있다.

변화하는 북극

북극은 2000년대 중반부터 급격하게 국제적인 관심을 받기 시작했다. 이는 크게 두 가지 요소에서 기인한다. 먼저, 북극에 전 세계가 공유할 수 있는 아직 발견되지 않은 다량의 석유 자원이 매장되어 있다는 새로운 관측 결과가 발표되었다. 두 번째는 북극의 만년설이 녹는 등 급격한 기후변화의 징후가 포착되었다는 것이다. 이로 인해, 지구 온난화가 지역 차원에서 환경에 어떠한 결과를 초래하는지에 대한 우려가 나타났고, 다른 한편으로는 북극해에 새로운 항로가 마련되리라는 기대감이 생겨났다.

2007년 초반에 강조되었던 경제적 기회와 환경에 대한 우려는 일부분 암울한 전망으로 바뀌었다. 러시아와 북극 인근 국가와의 관계가 악화되고 있는 상황에서, 2007년 8월 초 러시아가 북극 해저에 자국 국기를 꽂는 사건은 ‘경주’ 혹은 ‘북극을 둘러싼 거대한 전쟁’이라는 개념이 부상하는 계기가 되었다.

잘못된 예측에서부터 상황 변화에 이르기까지 여러가지 이유로 인해, 북극을 둘러싼 갈등에 대한 암울한 예측이나 클론다이크 (Klondike)에서의 석유 추출과 운송 등 그 어느 것도 실현되지 않았다. 경쟁 대신 협력이 주로 지역 관계를 형성했다. 미국이 셰일오일과 가스 생산을 시작하면서 발생한 국제석유시장의 변화, 그리고 부분적으로는 2014년부터 러시아의 국제투자를 제한하는 제재조치로 인해 대다수의 예측과 달리 대대적인 석유 채굴은 일어나지 않았다.

북극 운항 비즈니스

Polar Geography (1)의 2018년 기사에 의하면, 대한민국 부산에서 네덜란드 로테르담으로 이어지는 항로가 수에즈 운하를 거쳐가는 북동항로보다 29% 짧은 것으로 확인되었다 (7,667 vs. 10,744 해리). 이론 상으로 항로가 짧다는 것은 비용과 운송시간이 줄어든다는 의미이다.

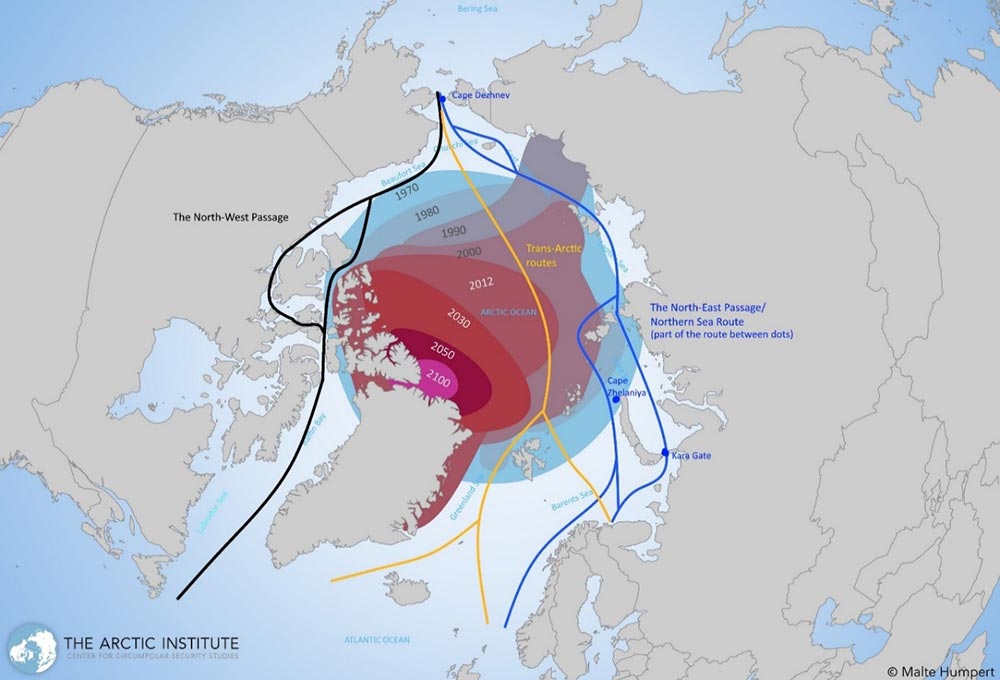

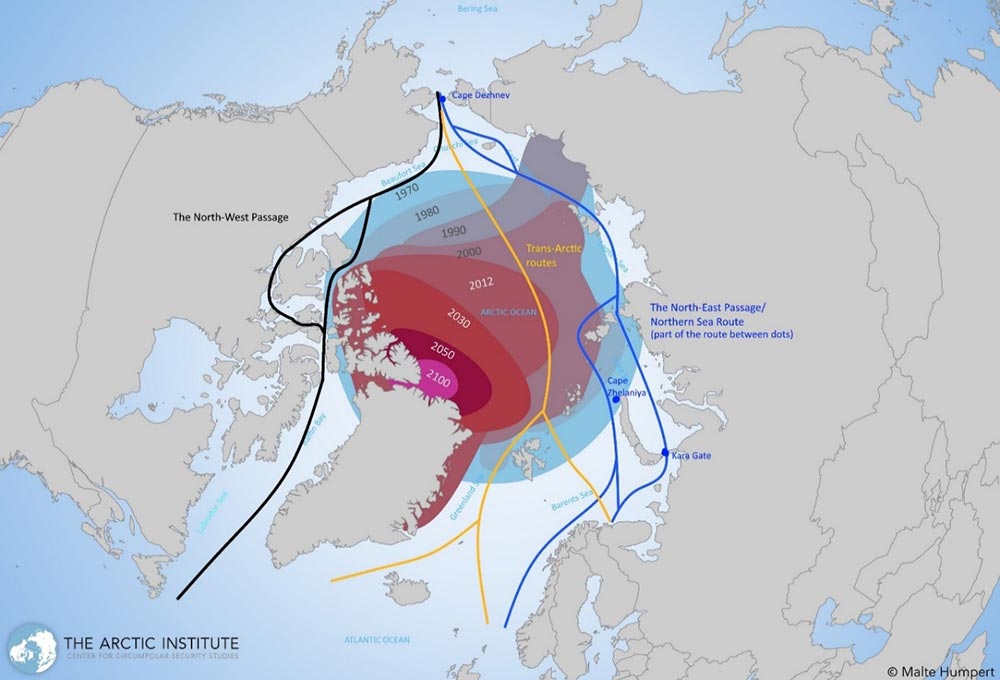

그림 1에 표시된 것처럼, 북미와 유라시아 해안을 따라 이어지는 북서항로와 북동항로 혹은 북극해를 가로지르는 항로를 예상 북극항로로 고려해 볼 수 있다. 이중 만년설이 계속해서 줄어든다는 가정으로 후자의 가능성이 커지고 있다. 본 글의 주요 주제인 북극해 항로 (NSR)는 러시아 노바야제믈랴 제도 (Novaya Zemlya)와 베링 해협 (Bering Strait) 사이에 있는 북동항로의 일부에 속한다.

그림 1 북극의 여름 만년설과 항로 예측

출처: Malte Humpert의 지도 일부 발췌, 항로 표시선과 설명글은 저자 첨부.

러시아의 증진 노력

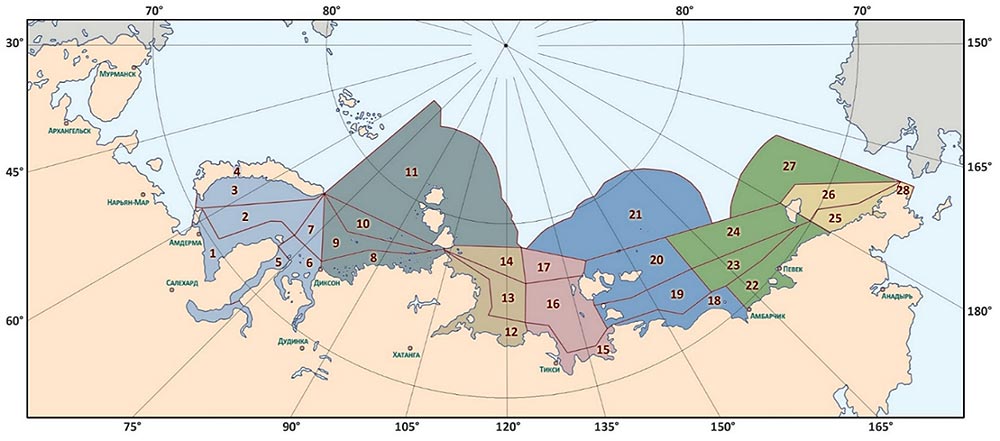

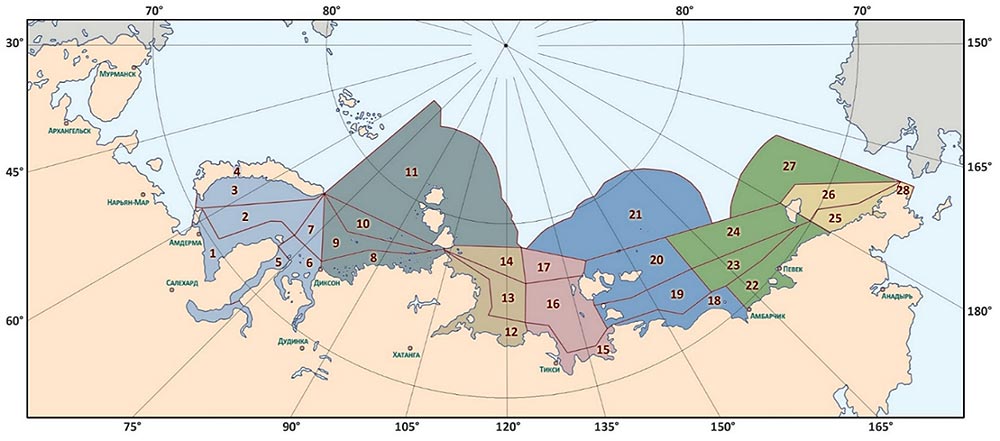

러시아는 북극 해상운송에 대한 긍정적인 전망을 환영했다. 러시아는 NSR 지역 운항을 위해 각국이 쇄빙선을 비롯해 자국이 제공하는 다양한 서비스를 이용하면서 잠재적인 이익이 발생할 것이라 예상했다 (그림2). Björn Gunnarsson과 Arild Moe가 Arctic Review on Law and Politics (2)에서 주목한 것처럼, 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령은 2011년 [NSR]을 전 세계 주요 상업적 항로로 부상시킬 계획이다’라고 말하며, 북극에 대한 러시아의 야망을 분명히 드러냈다. 이에 따라, NSR은 러시아 북극 전략의 우선 순위가 되었다.

러시아 정부는 이러한 목표를 달성하기 위해 NSR 통항을 실현시키기 위한 야심찬 프로그램에 착수했다. 러시아는 먼저 2019년 12월 2035 북극해 항로 개발계획 (Plan for the Development of the Northern Sea Route until 2035)을 채택했다. Atle Staalesen (3)이 설명한 것처럼, 해당 계획은 ‘북극해 항로 개척에 필요한 인프라 개발, 천연자원 매핑을 위한 선박 구축, 신규 인공위성 및 기상장비 발사에 이르기까지 광범위한 분야에 걸쳐 다양한 우선순위를 모두 포함하고 있다’. 그 중에서도 러시아 쇄빙선 함대를 확장하고, NSR에 걸쳐 비행장과 비행 기지를 신규 구축한다는 계획이 핵심 목표였다.

그림 2: 북극해 항로 지역

주: 지도에 표시된 숫자는 서브구간을 의미.

도전과제

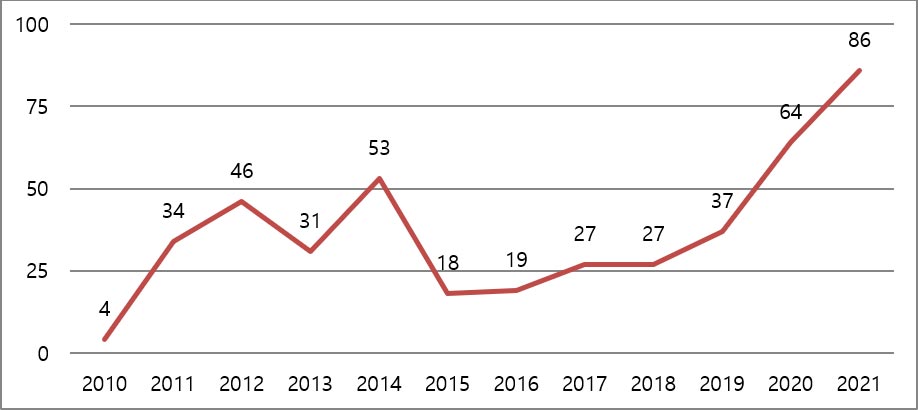

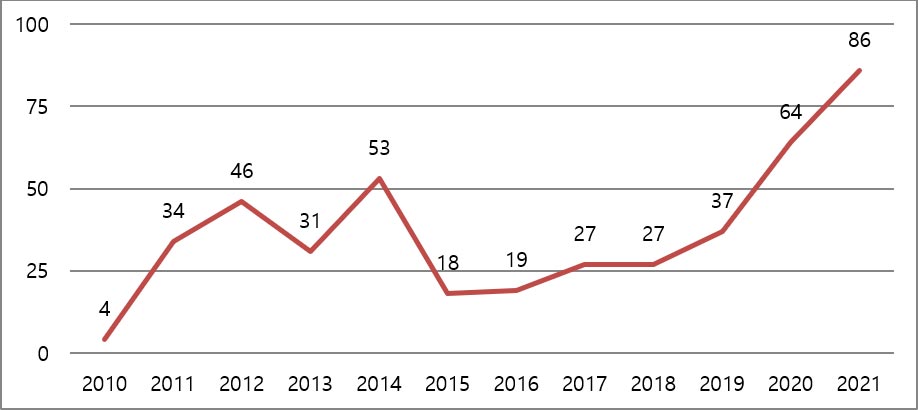

북극 해상운송이 급속하게 확대될 것이라는 대다수의 예측은 실현되지 않았다. 그림 2는 최초의 북극 운항이 시작된 2010년 이후 발전 추이를 보여준다. 도표에 표시된 증가치는 비율상으로는 높게 나타내지만, 매우 저조한 수준임을 알 수 있다. NSR의 연간 운송량은 최고치를 기록한 2021년에도 수에즈 운하와 파나마 운하의 물동량과 비교하면 매우 미미한 수준으로, 각 운하의 3일치 물동량 보다 적다.

그림 3 – 북극해 항로 – 물동량

주: 그림에 표시된 물동량은 러시아 국내항 (연안운송)간 운송과 러시아 북극해에서 NSR 외부로 향하는 목적지 운송을 모두 포함한다.

러시아의 증진 노력에도 불구하고 북극 해상운송에 대한 상업적 이득이 생각보다 크지 않은 원인은 여러가지로 파악해 볼 수 있다. 이 중 몇 가지는 다음과 같다. 첫째, 얼음이 없는 (ice-free) 북극해를 항해할 수 있는 기간이 여전히 길지 않다는 점이 문제로 지적된다. 경로를 재설정하기 위해서는 추가 비용이 발생하고, 운항 기간이 짧아 정기 노선을 변경하는 것 역시 수익이 줄어드는 원인이 된다. 현재 7월 말부터 11월 초까지 약 4개월간 운항이 가능하지만, 만년설이 계속 녹으면서 운항 가능 기간이 점점 길어질 것으로 예상된다.

빙하가 적다고 하더라도 여전히 예측하기 어려운 빙하 상태나 기후조건, 계절성 어둠, 글로벌 위성에 기반한 항해 및 통신시스템이 적용되는 지역이 제한되어 있어 북극 항로 운항은 여전히 기존 항로보다 예측이 어렵고 위험해 많은 보험비가 발생한다. 마지막으로, 2017년 도입된 국제해사기구 (International Maritime Organisation, IMO)의 극지선박기준으로 인해 극지방을 항해하는 선박과 선원 훈련 비용이 상승하게 되었다. 이에 따라, 북극항로 단축으로 인해 절감된 비용이 부분적으로 추가비용으로 인해 상쇄되는 결과로 이어지게 된다.

안보와 북극 해상운송

러시아에 있어 북극은 경제적 측면뿐만 아니라 안보 측면에서도 중요하게 작용한다. 러시아 탄도미사일 원자력 잠수함 (SSBN)의 대부분이 콜라 반도 (Kola Peninsula)에 주둔 중인 북방함대 (Northern Fleet)에 집중되어 있다. Arlid Moe는 2020년 The Polar Journal (4)에 기고한 글에서, 러시아가 안보 이해로 인해 NSR에 집중할 수밖에 없다고 지적한다. 여기에는 NSR을 따라 국가 주권 수호와 더욱 안전한 항해라는 이중목적을 수행할 군사기지와 민간기지를 건설한다는 계획이 포함된다.

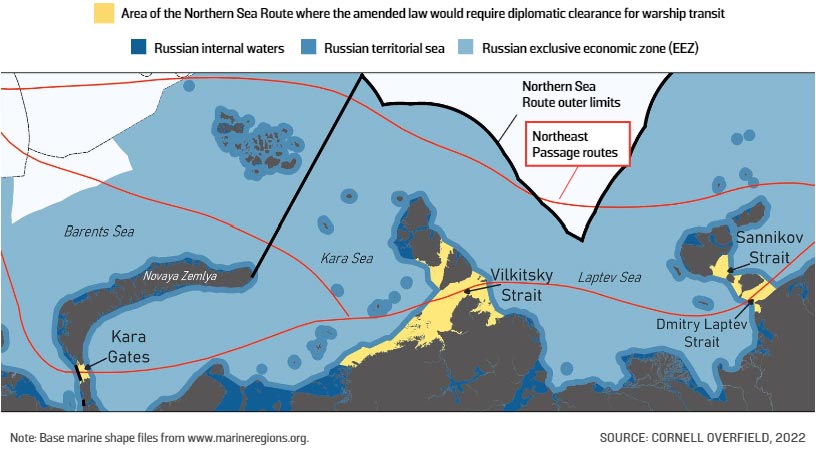

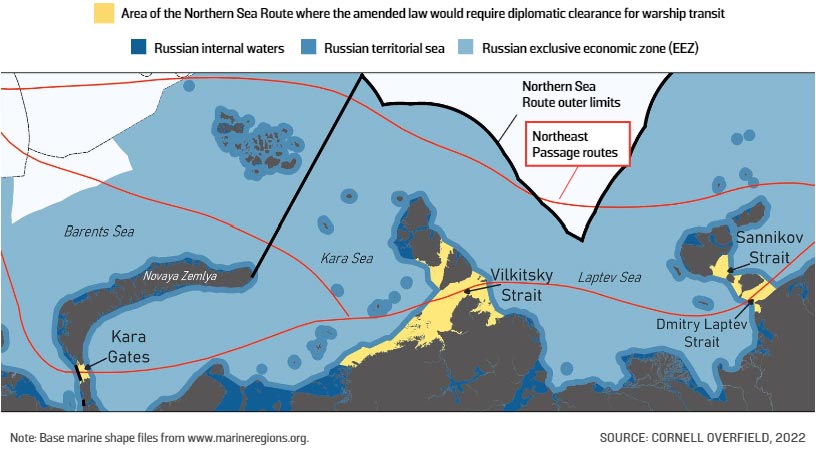

BSAH Rhône 프랑스 해군 물류선이 2018년 NSR을 통항한 이후 러시아는 러시아 북극해에서의 외국 군함 항해를 제한하려는 기존의 노력에 거듭 불을 지폈다. 블라디미르 푸틴 대통령은 2022년 12월 2019년 제안된 개정안에 서명했다. Cornell Overfield (5)이 설명한대로, 러시아는 해양법에 관한 유엔 협약 (유엔해양법협약, UNCLOS) 제 234조와 관련해 상기 자국법과 NSR 지역 항해 관련 규제에 의존하고 있다. 본 조항은 북극 연안 국가에 결빙 해역에 대한 확장된 권리를 제공한다. 러시아 개정법은 외국 선박이 NSR에 걸쳐 있는 4개 해협에 위치한 러시아 내수 (internal waters)를 항해하는 경우 러시아의 허가를 받아야 한다고 명시하고 있다 (그림 4참조).

그림4 – 2022년 러시아 개정법의 영향을 받는 지역

북서항로를 둘러싼 캐나다의 주장과 마찬가지로, 미국 역시 UNCLOS가 NSR에 걸친 해협을 비롯해 NSR 통항을 제한한다는 러시아의 주장을 일축하고 있다. 러시아가 우크라이나를 공격하고 크림반도 (Crimean Peninsula)를 합병한 2014년 이후 급속도로 관계가 악화되자, 미국은 러시아 북극해에서 공개적으로 항행의 자유작전 (FONOP) 전개를 고려하기 시작했다. FONOP는 남중국해 (South China Sea)에 대해 중국에 신호를 보내는 것처럼, 러시아의 주장에 대해 반대한다는 미국의 입장을 강조할 수 있다. 2022년 12월 러시아 법 개정이 미국의 이 같은 계획에 대해 어떠한 여파를 일으킬지는 앞으로 지켜봐야 하겠지만, 해당 개정법이 북극 운항의 안보 측면에 집중하고 있다는 사실만은 분명하다.

우크라이나 전쟁의 여파

2014년 대부분의 국가가 러시아에 대해 징벌적 제재조치를 취했고, 이로 인해 NSR 활용으로 얻을 수 있는 이득은 큰 타격을 받을 수밖에 없었다. 러시아는 북극해에서 생산되는 액화천연가스 (Liquified Natural Gas, LNG) 해상 수출을 위주로 목적지 운송을 우선시하고, 일부 중국의 이해를 부각해 환심을 사는 방법으로 대응했다. Gunnarsson과 Moe (2)가 언급한 것처럼, 2014년 이후 중국의 개입이 점차 증가했다. 2016-2019년 동안 중국의 코스코 (COSCO)는 러시아를 제외한 외국선박의 NSR 통항 전체의 45%를 차지했다. 또한, 2018년 초 자국의 북극 정책을 발표하면서 북극 해상 실크로드 (Polar Silk Road)를 일대일로 (Belt and Road Initiative) 이니셔티브에 포함시켰다.

러시아가 2022년 2월 우크라이나에 대한 공세를 강화하자 추가 제재가 뒤따랐고, 이로 인해 NSR은 엄청난 타격을 입게 된다. Malte Humpert (6)가 2022년 9월에 언급한 것처럼, ‘제재조치의 여파로 선박 운영사가 러시아를 회피하면서 10여 년 만에 처음으로 NSR은 국제 운송의 주요 항로로 운영되지 못하게 되었다’. NSR을 운항하는 유일한 외국 선박은 러시아 기업인 노바텍 (Novatek)이 주문한 LNG 운반선이었다 (대부분 한국에서 건조되었다).

중국 기업조차 한걸음 뒤로 물러섰다. Humpert가 지적한 것처럼, 2021년 COSCO는 ‘NSR을 통해 아시아와 유럽을 26차례 오간 것으로 기록되었으나’, 이듬해인 2022년에는 단 한 척도 운항하지 않은 것으로 파악되었다. 중국 기업 역시 러시아에 대한 국제사회의 제재에 대항하려는 위험을 피하려 했던 것으로 설명된다. 따라서, 적어도 단기적으로는 러시아의 NSR 개발 야심은 우크라이나 공격으로 치명타를 입은 것으로 보인다.

한국에 주는 시사점

앞에서 설명한 것처럼, 한국 역시 북극 해상운송에 관심을 보였다. 이명박, 문재인 전 대통령 역시 2012년과 2019년 노르웨이 방문 당시 이 점을 강조한 바 있다. 현대 글로비스는 2017년 10월 NSR을 최초로 통항한 한국 기업이 되었다. 이후 몇 년 동안 몇 차례의 항해가 이뤄졌다. 대우조선해양 (DSME)은 2013년 노바텍을 상대로 쇄빙 LNG 운반선 15척 수주에 성공했다.

Arild Moe와 Olav Schram Stokke (7)는 2019년 한국과 중국, 일본의 북극 해상운송에 대한 이해와 정책에 대한 연구에서 3국 중 ‘선박업과 해양운송을 중심으로 한국에 가장 많은 사업 기회가 놓여 있다’고 지적했다. 그러나, 북극에 대한 한국 정부의 우선순위는 기업을 통해 충분히 반영되지 못했다. Moe와 Stokke는 추가비용과 북극 해상운송의 복잡성, 그리고 사업과는 관련 없는 여러가지 요인으로 인해 이해가 제한된 측면이 있다고 지적했다.

러시아가 우크라이나를 침공한 2022년 2월 직후 한국은 국제법과 안보 위반에 대해 러시아에 대한 국제사회의 징벌적 제재에 동참했다. 이러한 제재는 북극해 통항을 통한 한국의 수출입 운송과 더불어 양국의 경제 관계를 중단시키는 결과를 가져왔다. 북극과 관련한 가장 대표적인 제재로, 대우해양조선은 러시아가 주문한 3척의 LNG선 건조를 취소했다. 한국은 북극을 둘러싼 안보 문제의 영향으로 엄청난 타격을 받았다.

우크라이나 전쟁과 관련된 제재조치가 얼마나 지속될지는 예측하기 어렵다. 이러한 여파가 지속되는 한, 북극 해상운송과 관련해 설정한 한국의 목표 달성은 어려워질 것이다. 여기서 던질 수 있는 질문은 다음과 같다: 그렇다면 어떻게 해야 할까? 한국은 북극 해상운송이 다시 재개될 수 있는 시점을 고려해 중장기적으로 주도적인 역할을 수행하도록 과학기술에 투자해야 한다. 결국, 빙하 상태로 인해 아직까지 분명하게 답하기는 어렵지만, 북극해를 가로지르는 북극항로는 여전히 시간과 비용 절감이라는 측면에서 가장 큰 가능성을 보여주고 있기 때문이다.

The Northern Sea Route – business, security and implications for South Korea

Paal Sigurd Hilde

Associate Professor

Norwegian Defence University College

Climate change has opened the Arctic in both a physical and political sense. While the physical opening has led to increased human activity, the political opening has brought international interest, but also global affairs into the region.

The ‘new Arctic’ that emerged in the mid-2000s garnered attention also in South Korea. It lead the country to seek observer status in the Arctic Council in 2008 – which was granted in 2013 – and to publish Arctic policy documents in 2013 and 2018. As one of the world’s largest shipping and shipbuilding countries, these themes featured prominently in the Korean ambitions. The Arctic represents not only an alternative and shorter route to the European market, but also an interesting market for the Korean shipbuilding industry.

This short article can offer no crystal ball vision of the future of Arctic shipping. It will, however, analyse business and security considerations that have been and will likely remain important in shaping its future prospects. Both today suggests that a significant growth in Arctic shipping is only likely in the medium to long term.

A changing Arctic

The mid-2000s saw a surge in international attention to the Arctic, initially spurred primarily by two factors. The first was the new assessment that the Arctic might contain a large share of global, undiscovered petroleum resources. The second was the signs of rapid climate change in the region, most evident in the shrinking of the Arctic ice cap. This fostered not only concern for the regional environmental consequences of global warming, but also interest in the opportunities afforded by the opening of new shipping routes in the Arctic Ocean.

In 2007, the initial emphasis on economic opportunities and environmental concerns was partly displaced by a more sinister perception. As relations between Russia and its Arctic neighbours deteriorated, the planting of a Russian flag on the sea floor at the North Pole in early August 2007, helped trigger the emergence of a notion of a ‘race’ or a ‘great game for the Arctic’.

For many reasons, ranging from misguided expectations to changing circumstances, neither the gloomy predictions for Arctic conflict, nor the predicted Klondike in petroleum extraction and shipping, have materialised. Cooperation rather than competition has marked regional relations. The absence of the petroleum bonanza many predicted was much due to the change in the international petroleum market with the advent of shale oil and gas production in the United States, and partly, from 2014, to sanctions limiting international investments in Russia.

The business of Arctic navigation

According to an estimate in a 2018 article in Polar Geography (1), the route from Busan in South Korea to Rotterdam in the Netherlands is 29 % shorter via the North-East Passage than that through the Suez Canal (7,667 vs. 10,744 nautical miles). In theory, the much shorter route means both lower costs and shorter transit times.

As figure 1 shows, the potential Arctic routes include the North-West and North-East passages along the North American and Eurasian coastlines respectively, as well as routes straight across the Arctic Ocean. The latter will become increasingly viable as the ice cap continues to shrink. The Northern Sea Route, which is the main topic of this article, is the part of the North-East Passage between the island Novaya Zemlya and the Bering Strait.

Figure 1 Predicted Arctic summer ice cap and shipping routes

Source: Adapted from Malte Humpert’s map: https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Summer-Ice-Extent-1970-2100-high-res.jpg Lines denoting shipping routes and explanatory text added by this author.

Russian promotion

Russia welcomed the optimistic predictions for Arctic shipping. It saw the potential for profiting from this, notably through the provision of Russian services such as icebreakers in the NSR area (figure 2). As Björn Gunnarsson and Arild Moe noted in Arctic Review on Law and Politics (2), Vladimir Putin made Russia’s ambition clear in 2011: ‘We are planning to turn [the NSR] into a key commercial route of global importance.’ Developing the NSR became a priority in Russian Arctic strategy.

To realise its goals, the Russian government embarked on an ambitious programme to enable navigation in the NSR. Most concretely, in December 2019, it adopted the Plan for the Development of the Northern Sea Route until 2035. As Atle Staalesen (3) observed: The plan ‘covers a wide range of priorities, from the development of needed infrastructure and building of new ships to the mapping of natural resources and launch of new satellites and meteorological equipment.’ Expanding Russia’s fleet of icebreakers and building new airfields and bases along the NSR, were key elements.

Figure 2: The Northern Sea Route area

Note: The numbers denote subareas. Source: https://nsr.rosatom.ru/en/official-information/boundaries-of-the-water-area-of-the-northern-sea-route

Challenges

The rapid expansion of Arctic shipping many predicted, has not materialised. Figure 2 shows the development since 2010, when the first international transit voyage took place. The growth is high in percentage terms, but from a very low level. Compared to the Suez and Panama canals, even at its peak in 2021, the annual number of NSR transits is vanishingly small; it represents less than three days of traffic in either canal.

Figure 3 – Northern Sea Route – transits

Note: Includes transits to and from Russian ports (cabotage) and destination shipping to and from Russian Arctic ports outside the NSR area. Based on data from Centre for High North Logistics (https://arctic-lio.com/category/statistics/)

There are several reasons why commercial interest in Arctic shipping has remained limited, despite Russia’s promotion efforts. I will briefly mention just a few. One is the still short, ice-free sailing season. As rerouting necessarily involves extra expense, a short season makes changing routes for regular traffic less profitable. Currently at about four months, from late July to early November, the season will, however, lengthen as the ice cap continues to shrink.

Even with less ice, unpredictable ice and weather conditions, seasonal darkness, and limited coverage for global, satellite-based navigational and communication systems, still make Arctic routes more unpredictable and riskier than using traditional routes – leading to higher insurance costs. Finally, the regulations of International Maritime Organisation’s Polar Code that came into force in 2017, make both the vessels themselves and crew training more expensive for polar navigation. The savings of a shorter Arctic route are thus partly eaten up by extra costs.

Security and Arctic shipping

In addition to its economic significance, the Arctic is important to Russia also for security reasons. Most significantly, the Northern Fleet based on the Kola Peninsula houses most of Russia’s missile-carrying strategic submarines (SSBNs). As Arild Moe emphasised in a 2020 article in The Polar Journal (4), security interests have influenced Russia’s approach to the NSR. This includes the construction of dual-purpose, military and civilian bases along the NSR – bases that enable both the protection of Russian sovereignty, and safer navigation.

After a French naval logistics vessel, the BSAH Rhône, sailed through the NSR in 2018, Russia renewed its traditional effort to limit the presence of foreign military vessels in the Russian Arctic. In December 2022, Putin signed an amended version of a law originally proposed in 2019. As Cornell Overfield (5) explains, Russia relies both in this law, and its regulation of navigation in the NSR area in general, on article 234 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The article gives coastal states extended rights in ice-covered waters. The new Russian law requires foreign state vessels to seek permission to pass through what Russia defines as its internal waters in four straits along the NSR (see figure 4).

Figure 4 – Areas affected by the December 2022 Russian law

Source: Cornell Overfield, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/20/russia-arctic-claims-territorial-internal-waters/

As with similar Canadian claims in the North-West Passage, the United States rejects Russian claims that UNCLOS allows it to limit navigation in the NSR, including in the straits along the route. As relations with Russia deteriorated sharply from 2014, when Russia attacked Ukraine and annexed the Crimean Peninsula, the United States started openly considering Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the Russian Arctic. A FONOP would underline the U.S.’ disagreement with Russian claims – as the United States signals China in the South China Sea. What effect the December 2022 Russian law will have on these plans remains to be seen. What is clear, is that the law highlights the security aspect of Arctic navigation.

The impact of the war in Ukraine

In 2014, many countries imposed punitive sanctions on Russia. Much due to this, interest in using the NSR suffered. Russia reacted partly by prioritising destination shipping, notably shipborne export of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) from the Arctic, and partly by courting Chinese interest. As Gunnarsson and Moe (2) show, Chinese involvement grew after 2014. In the period from 2016-2019, Chinese COSCO conducted 45 % of all non-Russian NSR transits. China made the ‘Polar Silk Road’ part of its Belt and Road Initiative with the publication of its Arctic policy in early 2018.

When Russia redoubled its aggression against Ukraine in February 2022, further and stricter sanctions were imposed. These hit the NSR hard. As Malte Humpert (6) noted in September 2022, for ‘the first time in more than a decade the NSR will not see international transits as operators avoid Russia as a result of sanctions.’ The only remaining, foreign flagged vessels have been LNG carriers employed by the Russian company Novatek (most of which were built in South Korea).

Even Chinese companies have stayed away. As Humpert pointed out, while COSCO in 2021 ‘completed a record 26 voyages between Asia and Europe via the NSR’, in 2022 it did not send a single vessel. A likely explanation is that also Chinese companies avoid challenging the sanctions against Russia. Thus, at least in the short run, Russia’s ambitions for developing the NSR have been fatally undercut by its aggression against Ukraine.

Implications for South Korea

As noted, Arctic shipping attracted interest also in South Korea. Presidents Lee Myung-bak and Moon Jae-In both emphasised this, for instance when visiting Norway in 2012 and 2019 respectively. The first Korean company to navigate the NSR, Hyundai Glovis, did so in October 2017. Several more voyages followed in subsequent years. Korean involvement also included shipbuilding. Notably, in 2013 Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME) won a contract to build 15 ice-breaking LNG carriers for Novatek.

In a 2019 study of Chinese, Japanese and Korean interests in and policies on Arctic shipping, Arild Moe and Olav Schram Stokke (7) found that among the three, ‘Korea has the greatest emphasis on business opportunities, highlighting shipbuilding and maritime transport’. The priority placed on the Arctic by the Korean government has, however, not been fully reflected among companies. Moe and Stokke found that business considerations related to the extra costs and complications of Arctic shipping – as well as other, unrelated business issues – limited their interest.

Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, South Korea joined the international sanctions that punish Russia for its violation of international law and security. The sanctions not only put a stop to shipping to and from South Korea through the Arctic, but also to South Korean economic relations with Russia. Most significantly from an Arctic perspective, the DSME cancelled three Russian orders for LNG-carriers. South Korea has thus been hit quite hard by the impact of security issues in the Arctic.

How long the war in Ukraine and the related sanctions will last, is impossible to predict. As long as they do, fulfilling the ambitions South Korea has set itself for Arctic shipping, will be hard. The question then becomes: What to do? One answer is that South Korea should invest in science and technology that will allow it to take a leading role when in the medium to long term, Arctic shipping again becomes possible. After all, it is trans-Arctic routes straight through the Arctic Ocean, which are still not viable due to ice conditions, that hold the biggest promise for time and cost saving.

- 악력

Dr. Raul Pedrozo is the Professor of the Law of Armed Conflict and of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College. He is also a U.S. representative to the International Group of Experts for the revision of the 1994 San Remo Manual on International Law Applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea. He served for 34 years as an active-duty uniformed service member, and served in numerous positions advising senior military and civilian defense officials. Professor Pedrozo received his Bachelor of Science degree in Police Administration from Eastern Kentucky University, and later earned his J.D. from Ohio State University and LL.M. from Georgetown University.

- 국내외 추천 참고자료

- 알림

- 본지에 실린 내용은 필자 개인의 견해이며 본 연구소의 공식 입장이 아닙니다.

- KIMS Periscope는 매월 1일, 11일, 21일에 카카오톡 채널과 이메일로 발송됩니다.

- KIMS Periscope는 안보, 외교 및 해양 분야의 현안 분석 및 전망을 제시합니다.

- KIMS Periscope는 기획 원고로 발행되어 자유기고를 받지 않고 있습니다.